I wrote the following text as a public note in my concert program of my compositions at Kid Ailack Hall in Tokyo the other day. I did not add any modifications since then. I wrote the note rather in a hurry, so there might be some parts that are difficult to understand or were not quite written with the right words. As for these issues, I would like to write more to explain better in the future.

In general, I probably prefer to raise an issue rather than

trying to find the answer to the solution. I am not a kind of person who likes

to deepen a thought based on some particular idea or system. If you read my

note, you may have an impression that I simply arranged casual thoughts that I

hit on. That is understandable. To be honest, I would like to leave in-depth

discussions to other people.

- Taku Sugimoto (November 11, 2005)

-----------------------------------------------------

About Philosophy of Silence

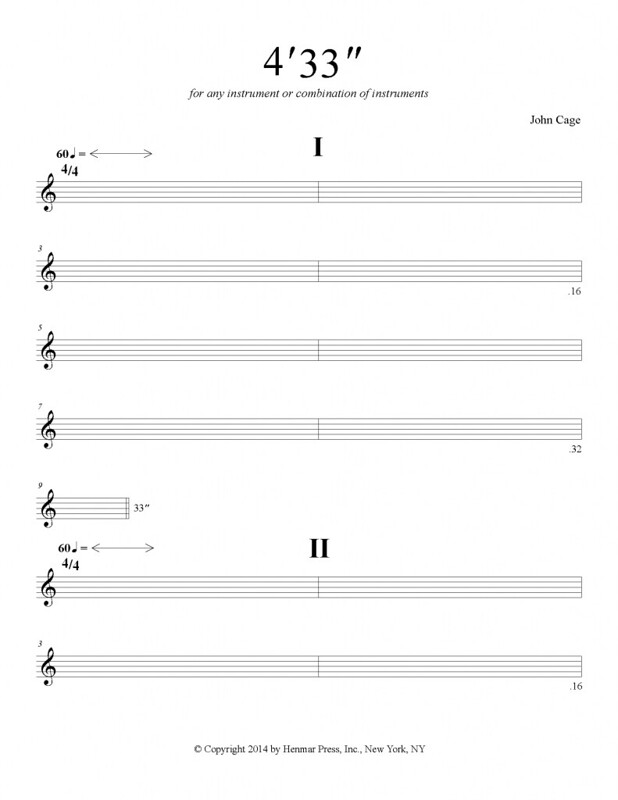

I often hear people saying that my music that is full of

intervals and gaps of silence must be just an adaptation of John Cage's works.

If I composed my works with more normal musical notes instead of so much

silence (that is exactly the thing most composers are doing - rehashing of

predecessors' old ideas), then people may not say that. Since there is a rest

in a series of musical notes, some people may say that I could simply use the

rests instead of silence. But that is a different issue. If there is a long

series of hundreds or thousands of rests without musical notes, the part will

be considered as a silence in most cases. And if the silence part lasts for

hundreds or thousands of measures, the part will be torn off from the structure

of music consequently, and the listeners' ears could be shifted to focus on the

environmental sounds naturally. But this is just the natural sequence of

events, and was not what John Cage had in his mind.

Then, what was silence to Cage? To put it simply, I guess it

was 'unintentional sound'. Then, what is unintentional sound? This question

seems to be quite contemporary, because I think that the current situation in

the music tends to involve sounds that are hard to tell whether they're

intentional or unintentional just from listening to the sound itself.

As Radu Malfatti also mentioned before, the idea of 'Silence

= Unintentional Sound' had existed even before Cage started to give meaning to

it, and the idea still exists now. However, the concept of 'silence' that had

already existed before Cage clearly started to change in a particular field of

music. How it has changed is the very interesting issue concerning the

contemporary sense of 'silence' that we are facing now.

From the present point of view, if a performer does not play

his/her instrument for a certain duration in a certain situation, that can be

considered to be his/her intention to let the listeners start to listen to the

environmental sounds (or to make the situation where environmental sounds can

be heard naturally). If the performer plays 4'33" and the audience knows

the concept of the piece, there will be a consensual situation where people

listen to unintentional sounds in silence. But in this situation, the

'unintentional sounds' are actually intended by incorporating the silent space

into the music intentionally.

Spaces are controlled by performers to some extent.

Otherwise, (it may sound odd but) the piece will not come into existence. In

fact, when a performer is going to play this kind of music, he/she has to

consider the environmental sounds and the noises from the audience (today's

definition of 'silence' must be this) as predictable factors to some extent.

Normally, silent music is performed in this way on the premise I mentioned

above. The situation might not be perfectly controlled, but genuine

'unintentional sound' does not exist in this situation either. How about in a

different situation? Would it be possible to play 4'33" on a stage where

musicians are playing some other music? If a musician plays 4'33" in the

middle of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra playing Beethoven, I guess that the

part might be still considered nothing but a part of Beethoven's piece even if

the musician insists that it was 4'33". However, this resembles in the

above-mentioned case, in the sense that the originally so-called 'unintentional

sound' was already included within a predictable range of events to some

extent. That is, there are so many ways to play Beethoven, and these different

ways are all considered to be within a predictable range. Conversely, to play

4'33" in the middle of Beethoven can be considered to be the similar event

as the environmental sounds in a point where the event was not controlled with100%

confidence. This consequence would also be inevitable when a performer is

playing sounds using an instrument. It is just a matter of degree. Whether it

is the sound of Beethoven's piece, or the environmental sounds, or the sound of

an instrument, there is no big difference in the point that the performer has a

rough sketch (plan) in mind in advance. (If so, isn't it possible to consider

that Beethoven's music has the silence - although we will face an obstacle in

this idea to overcome.) And will the unintentional listening become possible if

we get rid of the sketch/plan from our minds?

When we are listening to a particular piece, the only thing

that could determine whether it is 4'33", or Beethoven's music, or some

simple daily life sounds is the title of the music. However, I doubt that it

was just due to an ideological difference. If the concept of 'unintentional

listening' can only function relatively, and if the concept is related to all

the complicated processes of recognition, everything can be regarded as a

silence, and vice versa.

Well, after writing the preface like this, I would like to

add my tentative conclusion below. After that, I will just continue to write

with vigor.

First of all, as long as any kind of sound could be

intentional or unintentional, it will differ depending on the context whether

it should be regarded as a silence or not. I think that the sound itself does

not contain the information to be judged (if it is regarded as a silence or

not) any more.

Next, there is another issue: "Is it really necessary

for us to analyze whether a particular sound could be a silence or not when

listening to music or thinking about music?" I would like to express my

standpoint on this question as clear as I can.

There is of course a legitimate opinion that whether the

sound should be regarded as a silence or not, and whether it is intentional or

unintentional, are not big issues. The only thing that would matter is 'sound'

when we appreciate music, and how it should be recognized is not important.

Well, that might be true. It is hard to argue with it, but as my simple

question, is it really possible for a listener to 'just listen to the sound as

a simple sound'? If that is possible, that means this way of listening is exactly

the unintentional relation to the sound in a true sense. If so, every sound

could be regarded as something not worth bothering about (or a trivial matter).

Can music exist if this is the case? Music has been developed as a complex

relationship of sounds and something besides sounds. That is how music should

be. It is clearly a different issue whether a sound can exist just as a sound

or not, and whether we can recognize it as a sound or not.

I doubt if we could simply say that one particular sound is

more significant than other sounds. Is an E note more special than a D note? Is

the start-up sound of a computer more interesting than the sound of rain? If it

were possible for us to hear sound in such a simple manner, any of these sounds

would not be more than any other sound. When we listen to a series of sounds,

aren't we evaluating the information each sound delivers in relation with other

elements? I think that every sound - like an E note, the start-up sound of a

computer or the sound of rain - obtains a nature as a unique sound by its

relations with each other. The identity of the sound must be formed on the

basis of the common understanding of the sound to some extent.

If we define a particular sound that has a particular pitch

as the sound that contains a corresponding frequency, we can mathematically

prove the fact that (for example) a C note can be in harmony with an E note and

a G note by comparing the frequencies of the three. This data can be trusted in

regard to the consonance of sounds, but when perceiving consonance phenomena as

sensuous impressions, can this sensuous value be absolute? Conceivably, the

fact that the notes C, E and G are consonant with each other could be an

incidental event. There might have been a chance that these three notes would

not be regarded as the consonant sounds or a chord or the sounds with pitches.

There might also have been a possible chance that some completely different set

of notes - whatever it was - became the consonant sounds, which could have been

proved to be consonant mathematically by means of some different method (or

could be the same method in a narrow sense) of reading the frequencies. If that

had happened, the music would be a completely different form as it is now.

Perhaps within the possibilities, some new form of expression that is not

regarded as music today could be included, and it might not be impossible to

perform a stunt to aggressively insist that this is music. But in order to

justify this statement, we need a common concept on what can be defined as

music as an initial premise. In fact,

the notes C, E and G are considered to be consonant sounds in the premise we

share today, and the other sets of notes that have no relation with each other

do not gain important positions in today's world of consonant sounds. That is

because any thought experiment regarding music has to be carried out using the

foundation of the present situation of music. On the other hand, the aggressive

statement, to insist that some form of expression can be regarded as music even

when it seems far away from the conventional form of music, naturally derives

from the current situation surrounding the music. It should be possible enough

to recognize a particular sound as something different from how it was identified

in the past.

However, if some particular sound - whatever it is, like the

start-up sound of a computer or the sound of rain, anything can be substituted

for that - can be perceived as something different from how it used to be

identified, what does that mean? If a particular sound can be something else

while holding its original identity, we could simply give a new name to it. For

example, we could say, 'The sound of rain is the C note'. This is not so

absurd.

I am fascinated with the idea that the context of a sound

can be displaceable with different contexts, while the sound keeps its original

identity. It is not quite the same meaning as the diversity of interpretation, as

it's often referred to.

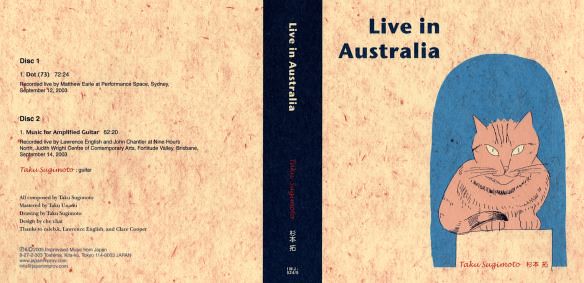

I will give a specific example, my album 'Live in Australia'. This is supposed to be my music recorded at my concert. The reason why this album is considered to be so is because I claimed so, and a certain system accepted that. But in a different context, it can be perceived as something else while holding the same contents of the sounds. For example, this concert was recorded by an Australian musician, Matthew Earle, so this album could be regarded as his field recording work that he has recorded in a certain situation. For him, my concert could have possibly been a performed 'silence' in my concert situation, and he could have possibly released the recording of the silence under the title of 4'33". Or it might have also been possible that some composer gave him a score on which the composer's direction was written as "Record a certain situation". Or there might have been a musician (or it could have been me) who plays a CD at his concert, and this was a record of him playing the full-length version of my album 'Live in Australia'. These examples show that it would be almost impossible for the listener to judge whose music it is - or what it is - from simply listening to the sounds whatever the music is.

Furthermore, the issue whether some recorded material has

strictly held to the original sounds or not should depend on the context. For

example, the claim that the sound quality of a MP3 file is bad should be made

on the presupposition that it is reproduced sound of a recording. But if the

same MP3 file was played as a part of some musician's performance, it is not

right to criticize the bad sound quality of the MP3 file (which contains the

same content as the previous case) recorded at the live concert. In these

cases, both MP3 files have exactly the same sound quality. When people hear some

sound and judge that it has poor sound quality, the judgment must only derive

from the listener's experience of listening to the same music with a different

context in a superior condition surrounding the music.

Some music is closely connected to a certain context. The

reason why Beethoven's pieces sound like Beethoven, or the environmental noises

sound like nothing but environmental

noises, may be related to this fact. This makes it possible for us to appreciate

music naturally. We can say the same thing as to silence. But isn't it too easy

for us to regard contemporary silence as the currently generalized idea of silence? Isn't it too simple to determine that

'silence' is equal to 'unintentional sounds'? Perhaps the silence in Cage's time

might have been unintentional, but in this present time, I think that the

silence can be also regarded as something intentional. More likely, the silence

has been used easily with some intention these days.

To go back to the initial subject, I would like to think

about silence and the musical rest in sheet music. When we listen to music in a

normal situation, we do not regard the rest as silence when the rest appears in

a certain pattern between the notes. For example, when quarter notes and

quarter rests alternate in the music, or when a whole note rest is repeated for

a rather long time, these rests will be recognized as a part of a certain

pattern. In both cases, or in most conventional music, the rests are necessary

materials in the structure of the music. But when we feel we are experiencing a

certain pattern in the music, the experience is restricted within a range in

which the notes and the rests are associated with each other in certain

patterns. Logically, the length of a quarter note can be one second or even one

hour, so we could claim and understand the music has a certain pattern, even in

an extreme situation where a one-hour rest follows a one-hour continuous note.

However, is the silence during the one-hour rest always the same? Of course,

nothing is different in an audio point of view. But when a certain context is

predominant, if we replace it with some other context, there will be some

change in our recognition. This change of our recognition must influence at

least somewhat how we listen to the music.

What if a long rest part is actually not a rest? If a long

continuous note is supposed to be a rest (for example, if the continuous noises

are coming from the refrigerator in the room), and if a long rest that is

regarded as a rest with no sound is filled with almost inaudible sounds that a

musician plays in a certain musical rhythm (in this case, if the sounds are

almost inaudible, it would not matter if the musician is playing some sounds or

not), our listening attitudes will be different. Whether we listen to the rest

or the silence assuming that it is the rest or the silence will definitely

change our mental attitude toward the music. It will differ depending on

whether it is a rest or silence. With this theory, there might be a chance that

the sound will stop being the same or stop holding its identity (this may be in

contradiction with what I wrote before, but if the identity of the sound itself

is formed on our recognition, it would be possible.)

The various issues I raised here may show that the concept

of silence needs to be revised (reconsidered) in this contemporary time. In the

shadow of the long path since Cage, there have been countless trials and

experiments and debates, all of which led us to new findings and new

possibilities in the history of music. For this reason, it is necessary to

practice some actual music in which one-hour notes alternate with one-hour

rests with various viewpoints. After this point, a new issue will emerge

naturally. This does not mean that there should not be an old concept of the

silence. There will still be the situation where the usual operations of the

most notes (or directly dealing with some sounds) including the rests are sufficient

enough to compose music. Of course there will be unusual attempts to make music

from now on, too. But beyond that, I think it is now about time to bring a

reinvention to our ways of recognition. This reinvention will come from the

issue of how to face the silence in this contemporary time. It is a result from

Cage's idea of silence, which has developed more intricately than his original

contemplation - which should be a blessing to us.

(Translation by Yuko Zama, July 2015)

(originally posted on the Improvised Music from Japan site in Japanese in December 2005: http://www.japanimprov.com/tsugimoto/tsugimotoj/essay3.html)

(originally posted on the Improvised Music from Japan site in Japanese in December 2005: http://www.japanimprov.com/tsugimoto/tsugimotoj/essay3.html)

No comments:

Post a Comment