by Michael Pisaro

Wandelweiser is a wordWandelweiser

Wandelweiser is a wordWandelweiser is a word for a particular group of people who have been committed, over the long term, to sharing their work and working together. I still find it something of a miracle that we discovered each other and have continued to function for over seventeen years: coming from different musical backgrounds, living in different parts of the world, and feeling free to go our separate ways when necessary. In fact, the “group” as such doesn’t ever come together as a whole, and includes others besides composers: musicians, artists, writers – friends. In Haan (near Düsseldorf) there is an office where scores are collected, the web site maintained, and recordings are released. This place, lovingly run by Antoine Beuger, is essential to the continued existence of the organization, but not to the deep connections that exist between us. Our sense of a shared mission is due, I think, to the countless beautiful musical and artistic moments we have experienced with each other.

Edition Wandelweiser was the name Burkhard Schlothauer gave to the fledging publishing and recording company he formed with Beuger in 1992. I guess it means “change signpost” if one understands it as a combination of

Wandel with

Wegweiser; or perhaps more literally, “change wisely”– (or, if one understands the second part as

Weise: wise man of change?) Whatever it means, I was never completely comfortable with the name, but have always understood it somewhat humorously – as something that just popped out of Burkhard’s linguistically inventive mind, rather than as a description of any kind of aesthetic program. (I’m pretty sure he was not trying to indicate that we were especially wise.) In any case, Antoine had recently met Jürg Frey, Chico Mello, Thomas Stiegler and Kunsu Shim and it must have seemed that they had enough in common (not just musically) to band together. They had a feeling that there had to be a way to do things outside of the rich, overconfident new music organizations in Germany and Switzerland, plus a sense of being outside of the status quo these organizations created. Over the years several more joined – including myself, Manfred Werder, Carlo Inderhees, Radu Malfatti, Marcus Kaiser, Eva-Maria Houben, Craig Shepard, André Möller, Anastassis Philippakopoulos (and several others who have since left: amongst them Makiko Nishikaze and Klaus Lang) and then, at some point, there seemed to be enough people, even though we kept meeting (many) other interesting musicians. (I will say more about this later.)

The first years of the organization were quite dynamic. Members came and went. For a while there were connections with Edition Thürmchen in Cologne and Edition Mikro in Zurich, two other publisher collectives of avant-garde music. For a period of about five years, starting in the mid-‘90s, Wandelweiser had an association with another performance and publishing group, named Zeitkratzer (the whole organization then was grouped under the umbrella of the English translation of that name: Timescraper). Burkhard was the only one who belonged to both groups. At the time Zeitkratzer (directed by Reinhold Friedl) was more oriented towards the live electronic side of the experimental music spectrum. Still, there was a fair amount of overlap between the two groups, as Zeitkratzer recorded works by Schlothauer, Malfatti and Beuger, and had as members, musicians such as Axel Dörner and Ulrich Krieger, who shared some aesthetic preferences with the composers in EW. After 2000 however the two groups went their separate ways. (Some associations continue – since 2007 Ulrich Krieger has taught at CalArts.)

Wandelweiser in 1992This was an exceptionally obscure stream of music in 1992 – almost invisible, at the edge even of the experimental avant-garde. There were no signs of it in North America or, as far as I know, anywhere outside of Germany and Switzerland. One would only have discovered it by accident.

Here is how I found out about it. Kunsu Shim – who, while no longer a part of Wandelweiser, was crucial to the aesthetic development of the group – was visiting Chicago in the fall of 1992 (with his partner, German composer Gerhard Stäbler). Kunsu, of Korean background, had lived for several years in Germany. He was very quiet (and slightly shy), but friendly – the opposite of the boisterous American “new music types” I knew at the time, and the first person I had met in a long time who wanted to talk about the music of John Cage and Morton Feldman.

Cage had been a visitor to Northwestern University, where I was teaching, for a few weeks in the spring of 1992. He had died in August of ’92 and his name was still very much in the air. At that time – and I think for most of the long period after

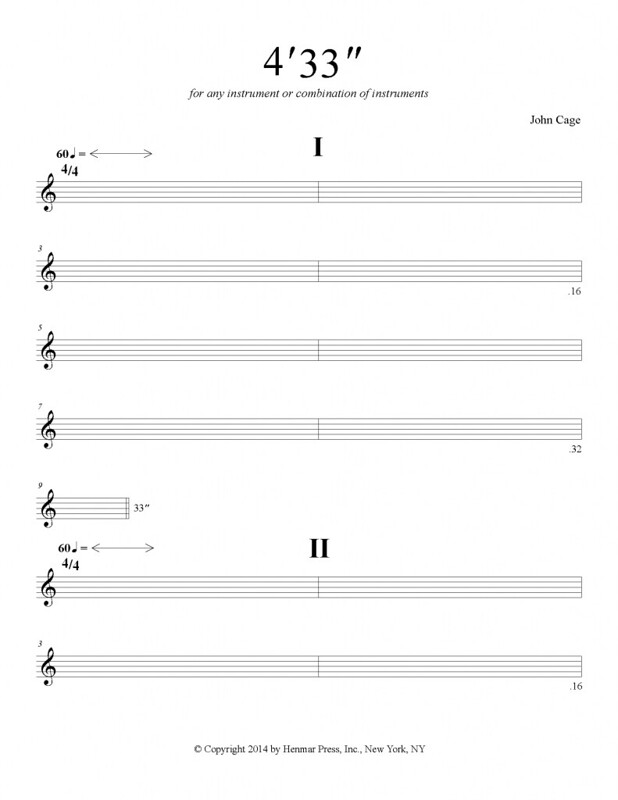

Silence was published (1961) – it seemed musicians were more interested in discussing Cage’s ideas than his music. For Kunsu, the music of Cage, and of those who worked with him and followed in his wake was felt to be more radical and more useful than the writing: because it had so many loose ends and live wires still to be explored (something I would also later encounter with other Wandelweiser composers). Thus

4’33” was seen not as a joke or a Zen koan or a philosophical statement: it was heard as music. It was also viewed as unfinished work in the best sense: it created new possibilities for the combination (and understanding) of sound and silence. Put simply, silence was a material and a disturbance of material at the same time.

In 1990 I had started to put relatively long silences into pieces, without really knowing why I was doing it. I wanted to stop telling musicians what to do in every detail and to start creating possibilities for performers to explore a particular, individual sense of sound within a simple clear structure I would provide. But I felt as if I was alone in these interests. Part of the circumstance behind Wandelweiser is the uncanny synchronicity: around that time several of us (including Kunsu, Antoine, Jürg, Manfred and Radu) were making more or less tentative stabs in this direction, without at all being aware that there were others doing it.

Kunsu Shim and my first encounter with silent musicKunsu gave me some tapes of his music. One consisted of a recent solo marimba piece called

…floating, song, feminine… (1992). There were hardly any sounds on that tape! I was instantly captivated. Tape hiss, a very few incidental noises (a chair, a cough, a few other unrecognizable sounds) and once in a great while a single short and abrupt marimba note, which seemed to appear out of nowhere: like the sharp tip of a pencil puncturing a sheet of paper, or a red balloon in a clear sky. (Later I would learn that the player was on a ladder and occasionally dropping mallets onto the keyboard. I’m not sure if this would have affected my response to the piece.) It was at once so clear, so simple that even a 3-year old would get it, and yet, simultaneously so mysterious and complex in its affect.

These early pieces by Kunsu, including in addition,

vague sensations of something vanishing (string quartet and contrabass, 1992),

marimba, bow, stone, player (1993),

expanding space in limited time (solo violin, 1994), and the

chamber pieces (1994) seemed to be putting the world on the head of a pin. In

expanding space in limited time the bow sometimes moves only half its length in five minutes. If you saw the violinist playing you would think he was a living sculpture installation instead of music. In a performance of the piece at Northwestern’s Pick-Staiger Hall in 1994 it took 20 minutes for me to hear any sound from the violin at all. Once I did start to hear it, over the course of the nearly two hours duration, the music became almost unbelievably rich: there seemed to be more sound, more tightly compacted in this miniature world, than in the statistical complexities of Xenakis (or the black metal of Burzum). The music also revealed the complexity of “silence” itself. Silence in music was not the cessation of sound, or even a gesture: it was a

different sound, one with more density than those sounds made by instruments.

No apology

Why do we like what we like? This is usually the most difficult point to explain.

Why would a schooled musician like myself, someone who grew up listening to and studying Jimi Hendrix and avant-rock, free jazz, and classical music suddenly decide that music with very little sound was the most exciting thing in the world? Basically every member of Wandelweiser has a version of this story. I’ve spent a lot of time pondering what it was that was so fascinating and inspiring about this piece (and the other pieces from this direction that I was beginning to hear). I have come to the conclusion that, while it’s possible to trace the moments that might have set the stage for such a reaction, the reaction itself is inexplicable. It is, at its root, not logical. It doesn’t follow from anything like a step-by-step process. You make a decision in a moment, and suddenly you’ve turned down one fork in the road. Terrifying and reassuring; strange and familiar; exciting and normal: all at once.

There’s no

reason to love this music. One just does (or one doesn’t). Aesthetics and history come after the fact. Essays (like this one) will not make you like it better and will not ultimately defend its continued existence. The last thing I would want to do is to

normalize something I continue to find strange.

Once one

has made the turn onto this strange road, a world of difference opens up. What looks like a narrow passageway from the entrance, turns out to have all kinds of byways, pathways, way stations — it becomes a world of its own. Small musical differences that to some might just seem like inflections (for example, the difference between a silence of 50 and of 60 seconds, or of a few decibels, or the difference in timbre between a low trombone or an e-bow guitar, or between digital silence and recorded silence) become intensely interesting to those working with them. Having had some training in just intonation, this was familiar: the difference between an equal tempered and a just (5/4) major third is for some unimportant, and for others of fundamental importance. (If someone says about a kind of music that it “all sounds the same,” it’s very likely to interest me. In my aesthetic experience it’s more enjoyable to make my own landscape out of things that are apparently the same, that to be given a group of diverse things that already stake out their own clear positions on the map.)

To finish the Kunsu storyThe recording of Kunsu’s music was definitely much farther in this direction than I had gone. Soon he had provided me with a few more of his scores along these lines (there weren’t many then) and a few recordings. It was then that I first encountered the music of Antoine (his incredible

lesen, hören: buch für stimme, for voice and tape from 1991) and Jürg (his very simple and beautiful

Invention for piano, from 1990). [Later it became clear that both Frey and Beuger had been moving in this direction for a while – Frey making gradual movements away, from the 1980’s onward, from his orientation in the New York School music of the 1960’s, and Beuger, who already in his teens had put silences into pieces, picking up composition again in the late 1980’s/early 1990’s with pieces such as

schweigen, hören for orchestra (1990) – very likely the first piece to sound like a “Wandelweiser” piece.]

Kunsu and I met again a little over a year later (1994, I think), and after that, unbeknownst to me, he took the liberty of sending Beuger some of my recent scores. A few months later I received a phone call from Antoine and we had a long conversation (anyone who has had the pleasure of one of these long phone talks with Antoine will know what an incredible experience that can be), at the end of which he asked if I was interested in joining the collective.

Shortly thereafter, on a trip to Germany, I met a group of the current (Antoine, Jürg, Burkhard, Chico, Thomas), and soon to be (Radu, Carlo) members for the first time. It was an incredible bunch of interesting, strong, diverse, stimulating, and very humorous people! It was like meeting up with some of Walter Zimmermann’s desert plants in the midst of the fertile high culture of central Europe (notwithstanding that some came originally from Korea, Brazil and unfashionable places in Switzerland, Austria and Holland).

Making sounds with StonesOne thing I took part in on that trip in the fall of 1995 was a recording of

Stones by Christian Wolff in the atelier of Burkhard Schlothauer’s apartment in Berlin. I love the disc, but the recording process itself was unforgettable. We had one rehearsal only: just enough to situate everyone to the recording environment and to see what people were doing. Each person made their own realization of the score, given minimal requirements from Antoine – I think ten sounds, however one wanted to understand that, to be made over the course of the 70 minutes duration of the recording. Naturally everyone had a different method of realizing the piece. Antoine had used chance procedures, and it had thrown up a need to make three sounds at once, quite a trick given the kinds of sounds he had chosen (involving balancing something and striking it in two different ways with stones simultaneously, if I remember correctly). This took some amusing acrobatics, but in the end came off successfully. Thomas Stiegler made every stone sound using his violin, intertwining pebbles with bow hair in the strings, dropping tiny stones on the body–it was like a miniature symphony in a violin. Burkhard dragged a large stone very gently over the floor of the atelier for a long, long time. Kunsu Shim’s sounds were all to occur within a period of about two minutes, 55 minutes into the recording. He sat without any visible motion (as far as we could tell, none whatsoever) for the first 55 minutes and then quietly, almost inaudibly, made ten extremely delicate sounds with a few very small pebbles and some cloth. Jürg Frey, as someone who had performed many pieces by Wolff, had determined, Wolff-style, to hinge a few of his sounds upon actions by others, unbeknownst to the people playing. By chance this had created a situation where the sign for the beginning of a sound and its end (i.e., the actions of two different performers) necessitated that he rub two good size stones over another gently for nearly half an hour. At the end of this Jürg was covered in white dust.

Listening to a Wandelweiser disc

Listening to a Wandelweiser discThe making of this recording and, especially the idea that we would

release such a thing (as happened in 1996) is reflective of one of the most important features of the thinking that was taking place within Wandelweiser. Obviously a recording is different in many ways from a live performance. The most profound difference in my view is how one experiences them. A concert is a series of moments in which something indefinable passes through sound and between people. The moments are sensuously immersive (sights, sounds, feelings, smells, tastes), but impermanent. But you have a relationship with a recording. It can be a brief relationship – and can then somewhat resemble a performance. But the best recordings are lasting in their own particular and repetitive way.

A recording is also an artifact that doesn’t care what you do with it. You can listen to the same song 500 times; you can refuse to open it (c.f. Brian Olewnick’s review of

Sectors (for Constant) by Sean Meehan); you can hang it on the wall, sell it or throw it away.

With recording, sound is stored for

use. How do you use a recording like

Stones? Do you just listen to it like anything else (perfectly possible in this case) or do you find ways of listening to it that suit the recording in other ways: say playing it all day at low volume (so that it can be forgotten, except for those very few moments when a sound rises to the surface, reminding you it’s still there). Or play it so loud that you hear

everything.

In other words, the recording can be viewed as

open, something like an instrument—a particular instrument that makes a limited set of sounds that can nonetheless have a variable relationship in the environment in which they are played. Although there are many discs in the Edition Wandelweiser catalog that can function as fairly normal listening experiences, their presence alongside those such as

Stones,

calme étendue (Spinoza),

Branches,

silent harmonies in discreet continuity,

exercise 15,

ein(e) ausführende(r) seiten 218 – 226,

phontaine,

Transparent City, and

im sefinental (to name only the most obvious in this direction), creates an interesting double trajectory: from the recording as

concept towards its use as music, and, conversely, the invitation to a listener to experiment in their own way with how to experience the more traditionally presented music. (I don’t mean to suggest that Wandelweiser owns or established this category – just that it plays a role in how I experience the music on any given EW disc.)

The first decadeSo, after a while, as concerts started to happen (in Düsseldorf, Aarau, Zürich, Munich, Chicago, etc.) and discs started to be released (with an initial onslaught of eight in 1996) some attention was given to the group in the German speaking new music press and at various music festivals. The presences of Radu Malfatti (I didn’t know any of his work as an improviser yet) and Manfred Werder (having just returned from a few years in Paris) made themselves felt. At this stage (late ‘90s) Wandelweiser seemed very much like a German thing — not just as a basis of operations but where most of the things were happening. This was ironic, inasmuch as most of the members were not from Germany. (I have to add here that the “Swiss contingent” of Jürg and Manfred did a lot to make sure that Wandelweiser was not

only a German thing, with many strong and memorable concert series in Aarau and Zürich.)

I’ve often wondered about this landing in Germany. It may have something to do with the high regard the American avant-garde was held in Europe, and in particular in Germany, compared to the status it had in the US at the time. It was often my impression that Cage, Feldman, Wolff, Lucier and the others had had a greater impact on the late 20th century musical life in central Europe than they had had in the US. The musical situation in the States, at least in classical and jazz music, had been flooded with more conciliatory voices: the minimalism of Glass and Reich, then the neo-Romantic attitudes struck by the majority of academic composers; in jazz this tendency was symbolized by Wynton Marsalis (coinciding with an apparent lack of momentum in free jazz, and very little improvised music to speak of). My friend, the musicologist Volker Straebel has called this period “the death of the American avant-garde” – and this was precisely what it felt like. So Europe in general, and Germany in particular, with its large resources for culture (even helping marginal enterprises like Wandelweiser) was more fertile ground.

There were two centers of Wandelweiser activity in Germany. Antoine, Kunsu, Marcus, André, Eva-Maria, percussionist Tobias Liebezeit, pianist John McAlpine, the artist Mauser, and for a while Carlo, his wife, Normisa Pereira da Silva and Radu all lived in and around Düsseldorf/Köln. Thomas Stiegler wasn’t too far away, in Frankfurt. Antoine has had an ongoing series at the Kunstraum in Düsseldorf since 1993. A huge number of Wandelweiser concerts have taken place there (the list itself would be a piece of a kind – just reading the way the titles change over the years is interesting – at least to me). There seemed to be just enough in the budget to bring musicians together, and so over the years many of us have come to feel that this place is a second musical home. (I just need to close my eyes to hear the sound of the rooms with Jürg Frey’s clarinet echoing through them.)

The artist Mauser (about whom more later) had his studio in nearby Cologne and this was another frequent performance location in the first decade. It was a very simple, fairly large and extremely pleasant studio space in the courtyard of an apartment building in a relatively quiet section of the city. Here the practice of daylong concerts (

Ein Tag), developed by Mauser and Antoine, really found its footing. For a while these were yearly – and incredible – events, where either very long pieces or collections of pieces would be done alongside time based work in other media: visual arts performance and installation, video, dance and so on. Many would come and spend a few hours there, to watch some of the performance, and to relax on the patio under the trellis and have

Kaffee und Kuchen. Others would spend nearly the whole time following the performance, even though often very little would be happening. Although I could only occasionally take part in events there, the days at Mauser’s are easily amongst my most memorable artistic experiences.

The other center of activity was Berlin. In the first decade the

Verlag (the German word for publishing company) was there, housed by Burkhard at his business. Recordings (such as

Stones) were made in Burkhard’s studio or in an old church near his house in the countryside a few hours away (Hohenferchesar). Former members Makiko Nishikaze, Chico Mello and Klaus Lang also lived in Berlin, at least part of the year. I was close by for the better part of a year in 1998/1999 on a fellowship from Künstlerhof Schreyahn. The musicologist and close friend to several in the group, Volker Straebel lives there. At the end of 1996 Carlo moved to Berlin. There, along with artist Christoph Nicolaus, he created one of the “founding” Wandelweiser situations. This project, called

3 jahre – 156 musikalische ereignisse – eine skulptur (3 years – 156 musical events – one sculpture) took place in the choir loft of the Zionskirche (in

Mitte, directly across the street from Carlo, Normisa and their young son Matheo’s apartment), every Tuesday for 3 years, always promptly at 7:30 p.m. Each concert featured the premiere of a new 10-minute solo piece (plus the rotation of one of the pieces of Nicolaus' sculpture – which consisted of stone posts of various lengths laid on the old wood floor of the balcony). Although some friends outside the group wrote works (including amongst others, Peter Ablinger and Wolfgang von Schweinitz), the overwhelming majority of the new pieces came from Wandelweiser composers. I’d venture to say that if you see a ten-minute solo piece in the EW catalog from 1997 to 1999 it was written for this project. Cumulatively over the three years, thousands of people came to the concerts, and had their first experience of this music. Peter Ablinger once described to me his pleasure at taking an hour ride in the U-Bahn to hear a ten-minute concert (with a trip to a café or pub afterwards – where often long discussions would ensue).

In any case, even in Germany, we had to exist on a shoestring. All the discs and the performances (after the initial round) only happened because individuals in the group found a small opportunity to do something. A free space close by; the interest of a few creative performers; a little grant money: in sum nothing that would come close to funding an average size music festival, would be enough for several densely packed Wandelweiser events. (A typical example would be a week in Düsseldorf with concerts every evening and two on Saturday and Sunday – with new pieces being rehearsed by various groupings of the ensemble.)

When I look back over all the events that took place over the years (certainly in the hundreds, with probably close to one thousand pieces performed) I am amazed by how much can be done with little or no money (still pretty much the case) and relatively little public attention.

Different aesthetics under one roofAt this point I think I need to mention that Wandelweiser does not embody, as far as I’m concerned, a single aesthetic stance. To be sure, from the outside there appear to be a set of shared characteristics, including an interest in silence, duration and radical extension of Cagean ideas and the work that followed from it. In fact, fourteen years ago, these might have been terms more easily applied to (much of) the music – but even then there were lots of different ideas about where the music was going as well as important differences in taste and philosophical stance.

Here is a list of some of the things I can remember discussing with people in the first years (and this might help to suggest how diverse the set of influences and conditions were):

• There were several different ideas about which works of Cage were most valuable. It wasn’t only

4’33”, but the number pieces,

0’00”,

Roaratorio,

Music for __, the

Variations,

Empty Words,

Cheap Imitation, the

String Quartet (in Four Parts). What seemed to be at stake here was not only the status of silence, but of the relationship between silence and noise (“the noise of the world”), and the function of tone within that continuum. Beuger’s important essay

Grundsätzliche Entscheidungen (1997) deals directly with this issue.

• The music of Wolff was critical for many of us. Christian was at the meeting in Boswil in 1991, where Antoine met Jürg Frey and Chico Mello. (Jakob Ullmann, Urs Peter Schneider, Ernstalberecht Stiebler and Dieter Schnebel were also there. Manfred Werder was in the audience for one of the performances.) Wolff has also been a great supporter of our music and many of us have worked closely with him on his (and our) music. Much of his music attempts to tap into the creative power of performance in an explicit way. Christian had been close friends with Cornelius Cardew, had worked with the Scratch Orchestra and had played with AMM – but this feature had been present in his music already quite early on, for instance in his

For 1, 2 or 3 People (1964). While I would not call what happens in this piece improvisation, it does involve on the spot decision-making that people who have worked in improvised situations would immediately recognize. At the root, and this I think applies even more to Wolff’s music (where it has been pursued in many different ways) than Cage’s, there is an understanding of a composition as a stopping point, as opposed to an endpoint, in the whole process of creating music. For many of us (all of us?), Wolff proved a deeper source of inspiration for making new work than Feldman. (Which is not to say that Feldman’s work is not beautiful or helpful for some of us–it is.)

• There was, early on, and continues to be an ongoing curiosity about the depth and breadth of the experimental tradition, American or otherwise, with a special interest in some of the radical and obscure works. Antoine is especially gifted at uncovering little known, radical work. I first learned of Tomasz Sikorski, Michael von Biel, Maria Eichhorn, Robert Lax, Alain Badiou and even Douglas Huebler from him (this list could go on much longer). Thanks to Antoine, at one recent Wandelweiser event, Terry Jennings’

Piano Piece (1960) was performed and seemed to be right at home amongst pieces by some of us. At a concert in Neufelden (near Linz) this summer, the Wandelweiser Composers Ensemble played Toshi Ichiyanagi’s

Sapporo (1962) and it almost felt as if it had been written for us to play.

• We have had occasional (but ongoing) discussions about the various directions jazz and improvised music has taken in the previous 30 years. This was important in the sense that it intersects in so many ways with the notions of indeterminacy. Radu, having worked his way from Jack Teagarden to Paul Rutherford and then beyond, brought a lot of experience and opinion to these discussions. But for myself as well, growing up in Chicago, playing jazz guitar, and hearing so much of the music of the various AACM combinations, this was an especially important issue. At the beginning there was little idea that what we were doing had much in common with what was going on improvised music – this would come later.

• There was a definite awareness of the importance of the German avant-garde: especially Helmut Lachenmann (with whom Kunsu had studied) and Matthias Spahlinger (with whom Thomas Stiegler had studied). From early on, some of the thinking about instruments and the use of sound, and above all, instrumental noise, was influenced in audible ways by these important figures.

As kind of a counterbalance there was an interest in many various small and strange things: art and music made by the various members of Fluxus, odd bits of poetry (Hans Faverey, Robert Creeley, Fernando Pessoa), the work of the Gugging artists and poets (especially Oswald Tschirtner) or, especially in my case, American vernacular music of the 1920’s and 1930’s (Harry Smith territory). For me these various oddball streams came together in the one-of-a-kind poetic work of Italian/Austrian poet Oswald Egger (who was introduced to Antoine through the publisher Thomas Howeg, Zurich).

• Over the years there have been many discussions amongst us concerning fundamental issues in making music. Because some of the ideas in the pieces attempt, in their own way, to get to the root of a particular musical situation, sometimes it has been helpful to use thought from outside. As Gilles Deleuze points out, philosophy has been, over the last three millennia, the main source of concept creation. (Science and mathematics in his view create “functions,” and art creates “percepts” – sensuous objects to be perceived.)

Each of us, without being anything like a professional philosopher (we’re more like non-professional philosophy readers), has drawn inspiration from philosophical work. This is very hard to talk about in depth without sounding pretentious, so I’m not going to. However, not mentioning it also seemed wrong – it’s an important part of the Wandelweiser atmosphere.

The conceptual background is present in a lot of the work we have shared (again, especially at first). I think it partially explains why, over certain periods an intense amount of activity was centered in one particular area of musical creation.

For a period in the mid- to late 1990’s there was a lot of work done, by several different composers, on the solo piece. Behind it is, I think, an interest in the number 1. This led to a great number of very diverse pieces: exploring the unit of time structure (

first music for marcia hafif,

stück 1998,

für sich), being alone (

tout à fait solitaire), the sonic features of one instrument (

die geschichte des sandkorns,

kammerkomplex,

mind is moving,

die temperatur der bedeutung), an expanse of limitless time (

calme étendue,

ein(e) ausführende(r)) or the disappearance of perceived time altogether (

ins ungebundene,

a certain species of eternity) – to mention a few of the many works. One thing that has always been striking about this work to me, is the tangible presence of the performer when

not playing. This is something that is never communicated on a recording – the continuity of the sound and silence is borne by the particular person, whose singular presence is more important than anything written on the page.

At some point the duo (or “twoness”) came into something of a focus (early on, mostly in the work of Jürg Frey, but then most recently by Beuger). Looking at the pieces, one sees a world of difference between 1 and 2, in musical terms. It’s hard to avoid the idea that two in music always implies, at the very least, relationship – if not love. [

Lovaty,

zwischen,

dedekind duos,

2 ausführende, and

two/too.]

The most important conversationMany important exchanges happened during the rehearsal process. We all spent a great deal of time getting to know each other’s music by playing it. The Wandelweiser Composers Ensemble is a group of sympathetic performers who nonetheless bring their own styles of playing and thinking. One writes for individuals rather than instruments. When Antoine, Jürg, Radu, Manfred or Marcus play on one of my compositions, I know that their musical character will permeate the work. And I know that their way of playing it will tell me things about my own piece that I could not have known without them. Even the simplest looking piece takes on a curious afterlife, as one sorts through what happened to it in the hands of one's friends.

As Jürg Frey has said: the most important conversations took place not in words, but in the music itself, from one piece to another; with one person going a different direction with very similar material to what the other had used. Seen in this way, it is only by getting inside the individual works that one sees the energy that is at play amongst this group of musicians: where notions of what is similar and what is different are replaced by much more complicated (and interesting) trajectories and tensions.

Radu brilliantly summarized to me the coming together, the commonality and the differences in this way:

I think that these things [i.e., the ideas of what we were doing] are there anyway and that "creative" people are only those who pick it up earlier then the rest, or hear it, or feel it sooner. In the Wandelweiser situation: Who started it? Who is a "follower"? I think we all started to become interested in similar things, even coming from very different angles and directions and therefore we met and got together and felt a mutual understanding right away.

A river deltaThat’s the image I can best use to describe what has started to happen as a result of all these conversations over the years, as our work has developed. What might have seemed at first like something of a single narrow stream, has proved to be capable of some variety. Early on, I took pleasure in the fact that I was never quite sure exactly whose piece I was hearing. The overlap and the sense of a truly shared language was exciting and inspiring. Now I take pleasure in being able to recognize, sooner rather than later, whose piece it is – even as it continues to be part of the same stream.

ArtAntoine introduced me to the monochrome painting of Marcia Hafif, an American artist. The idea behind this work was that “one” kind of material (that is, one color and kind of paint) was already multiple. It is, abstractly, one color, but in reality, when the paint is applied to the canvas by hand, there are many miniscule variations in tone and texture. The fact that the description was simple but the reality complex, did not fall on blind eyes or deaf ears. It is interesting how revealing a choice of a favorite artist can be. Jürg Frey loves the still life painting of Giorgio Morandi: and thus it becomes possible to see in his work the subtle, careful, endless shift of the same basic material – each time somehow just new enough to engage you, and to make you more deeply aware of the possibilities for expression with limited means. It won’t surprise anyone that Manfred Werder is fascinated by the conceptual artists. I can remember him reading Lucy Lippard’s

Six Years: The dematerialization of the art object from 1966 to 1972 like it was a suspense novel. Carlo Inderhees has been influenced by the work of On Kawara. (That makes sense, doesn’t it?) Although I love all this art, recently my own tastes run to James Turrell, Juan Muñoz and some of the installations of Sarah Sze. As these exchanges started, I had the sense that much had happened in the realm of the visual arts that had no parallel with developments in music (Carl Andre, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Dan Flavin, Agnes Martin, etc.). Perhaps, with all of the interesting work done in experimental music in the last 15 years, this has started to change.

The presence of one artist-musician and two great artist friends of Wandelweiser is a very significant (if in the US, seldom visible) part of the group.

Mauser introduced himself to Antoine at a concert of John Cage’s in Cologne in the early 1990’s. His work, which kept evolving right up until his death in 2006, was a significant part of the Wandelweiser environment. Entering Mauser’s studio for the first time in 1995, I at first thought it was devoid of art. As we sat and talked, the sun shifted and I became aware of very light, somehow luminous squares on the walls. At some point it was clear that they weren’t just effects of the light, but artworks: very fine translucent paper had been fixed to the wall, and the paper caught light to varying degrees, depending upon the angle with which the light hit it. Could anything be simpler? But nothing is as easy as it looks. The art appeared and disappeared magically and seemed to have its own un-emphatic duration. It had taken Mauser decades of very hard work, filled with uncertainty, to arrive at this solution: at once clear in concept and unbelievably sensual (you took it all in with your eyes before your brain started working). It became a model for musical work for some of us.

The artist Christoph Nicolaus has been a close friend to several in the group for nearly as long as it has existed. Christoph does many kinds of work: drawing, photography, video and other media. Much of his work is durational in nature: collecting single drops of water from various sources every day and storing them in glass containers (where they create beautiful “clouds” of evaporation); photographing the same location at the same times every year (in spring, summer, fall and winter); making a daily drawing using the sun and a magnifying glass to burn narrow, straight lines onto paper (dark brown images which nonetheless retain the luminosity of the sun). With his ongoing series

Garonne, he is making a very large set of videos of rivers (having already covered much of the world to do this) according to a very simple principle: finding a bridge and filming directly down on both sides, using autofocus, as long as the battery holds out (thus creating a series of ca. 60 minute videos, paired for each river, with water flowing from the top to the bottom of the screen in one, and from the bottom to top of the screen in the other). An installation presents a collection of 2 to 6 rivers shown simultaneously, chosen at random from the pile. The differences are astounding: the colors (all shades of green, brown, black, orange and blue), the flow, the wind and weather, the kinds of debris – one would never imagine how singular each river could appear. One of my favorite Wandelweiser events was the exhibition of these videos in Berlin in 1998, simultaneous with Carlo’s solo cello piece

für sich. Carlo’s music and Christoph’s videos were in profound harmony – something “multi-media” art often strives for, but rarely achieves. Nicolaus has installed a beautiful collection of Mauser’s work in his large apartment in Munich and hosts monthly concerts there under the title

Klang im Turm. It is one of the central current locations for Wandelweiser events.

The least classifiable member of Wandelweiser is Marcus Kaiser. He is a cellist–painter–architect–composer–builder/designer–maker of sound pieces–video artist. Marcus does not juggle these activities – he works on all of them simultaneously as if they were part of some vast rhizomatic assemblage. He paints jungles the way they grow: adding layer after layer of green until it is nearly a monochrome. He records individual layers of sound regularly over the course of many days, until, when simultaneously played back, these recordings reach a point of near saturation (in which, however, sonic features remain distinguishable). He designs desks that serve as workspaces in a communal environment. His work is grand in scope, but not oversized; it is bold, but presented with gentleness and humility. (These last two are deeply personal qualities that anyone who knows Marcus will recognize.)

Mild weather / distant thunder (Wandelweiser events)Although over the years there has been great variety in the location, structure and personnel involved in the concerts, the character of a Wandelweiser event has some constants: A great deal of music; many discussions; the feeling of good-natured friendship and community.

A strong reaction from someone else (“I really did/did not like that, and here’s why.”) can serve to clarify one’s own thinking. However, in my experience the interactions that emerged from Wandelweiser events, have usually taken place in an atmosphere of general support — where it is a given that one would continue to care about and for the other, regardless of aesthetic differences.

Antoine, who in Düsseldorf has staged more large-scale Wandelweiser events than any of the rest of us, has always been particularly clear in his feelings about this matter (and is himself a good model for the attitude): people should not feel “wounded” by presenting their work or ideas. Critique does happen, but to me it has seemed rather far down the list of things to accomplish during one of these gatherings. In any case, with a group of close friends, one usually knows how they feel about one's work. Over the long run, sympathies and differences will make themselves clear in the decisions made in the work itself (as if individual works were part of larger picture). For instance, starting in the mid-90’s one could follow the use of the bass (or low) drum duo from work to work, composer to composer:

Ohne Titel (für Agnes Martin) (Frey, 1994/95),

fourth music for marcia hafif no. 3 (Beuger, 1997),

time, presence, movement / one sound (Pisaro, 1997) – finally becoming four such instruments in Malfatti’s

l'effaçage (2001). A close look at these four apparently similar pieces would reveal subtle but substantial differences in approach. Although each piece can stand alone, there is also a (wordless) discussion going on between them. There are many such discussions in the Wandelweiser catalog.

None of this means that striking events are avoided — quite the contrary. But these tend to be shocks produced by the works themselves. If I think about some of these: the first time I experienced Beuger’s nine hour composition,

calme étendue; the endless (and occasionally hilarious) stream of Swiss birds and valleys in Jürg Frey’s

Lovaty; the way the density of Marcus Kaiser’s incredible jungle paintings permeates his cello playing; the radical juxtaposition of control and freedom in Radu’s

Düsseldorf Vielfaches; the 15-second summary of the orchestral experience contained in Manfred Werder’s

2008-1 (just to mention the first five that come to mind), shook me as an artist in a way no harsh words could ever do. I’m still dealing with these events. (In part, my summer two-week festival,

the dog star orchestra, is an attempt to find some kind of North American / West Coast parallel to these concert meetings.)

Beyond the creative impetus received from discussions and exchanges of ideas, there was, above all, the pleasure of wonderful performances of the music. In addition to the members of the Wandelweiser Composers Ensemble, we have each been very lucky to work with performers whose dedication to the music and to the people making it is responsible in part for the continuity of the work being made.

Here I tip my hat to a special group of musicians who have kept faith for many years in a spirit of friendship and generosity: pianist John McAlpine, percussionist Tobias Liebezeit, oboist Kathryn Pisaro, speaker Sandra Schimag, accordionist Edwin Alexander Buchholz, the Quatour Bozzini (Clemens Merkel, Nadia Francavilla and Isabelle and Stéphanie Bozzini), violist Julia Eckhardt of Q-02 and Incidental Music, flutist Normisa Pereira da Silva, cellist Stefan Thut, percussionist Greg Stuart, pianist Jongah Yoon, pianist Guy Vandromme and saxophonist Ulrich Krieger. I can’t imagine our music without the creative participation of these people.

A few statements about composition (concepts, structures, sounds)Let us call a musical concept an idea or thought about music at some remove from the embodiment of the thing itself.

A written composition contains a concept of how a particular music should be made. (In this way, all written music is conceptual.)

In a composition, a small, clear concept might be preferred to a large, overarching one. (For this way of thinking, better a piece that takes up the simple coincidence or non-coincidence of two players than one that seeks to redefine orchestration.)

There is greater diversity to be found in a collection of clear concepts than in a collection of overarching ones.

Clear concepts can sometimes lead to perplexing results: results that test the powers of perception on some level and are conscious of that test. One kind of sonic pleasure is connected to the effort the mind of the listener makes to understand (or properly hear) the sound situation initiated by the composition.

The musical situation will get

some degree of its structure from the composition; but the composition cannot account for everything. In the written work, something might be said about the time, or sound, or player or instrument (or all of these), but it is essential to keep in mind that much (most?) of the sonic reality will occur in the situation itself.

The performers of the work are capable of being aware of the concept and the structure given by the composition, and of making active decisions at the same time.

There is no clear and logical way to affix a percentage of creation or responsibility to any one of the musical actors. The music arises as a result of a whole set of circumstances, almost as if, once set in motion, it is doing the acting and the thinking.

The process described here is

independent of conventional notions of what might or might not sound good, what is easy or difficult to grasp, or what is easy or difficult to listen to.

At its best the surface of the music (i.e., the sounding result) will be engaging enough to draw a listener into the world of the piece. It is

inside this world in that significant artistic events (moments that can alter the way we hear and understand music) transpire.

There is nothing wrong with a beautiful surface, placid and composed, despite its contact with musical upheaval.

Where are we now?

Where are we now? Over the years the network of people associated with Wandelweiser has expanded. The regular concerts taking place in Aarau, Düsseldorf, Munich, Zürich, and Los Angeles, along with semi-regular ones in New York, Berlin, London, Vienna, Chicago and Tokyo have done a lot to make people aware of the music and to draw people to it. Given that new music is being written constantly and then performed, the concerts are still the frontline of activity (and represent much more than could ever be recorded and released).

As is probably already clear, the openness of much of this work to environmental sound, its more than occasional extended duration, and the frequent use of indeterminacy means that in most cases there is no such thing as a “repeat” performance: the second performance of a piece (in a different context or with different performers) can feel like another premiere. So we all, even after all these years, continue to find many reasons to perform each other’s work, and often serve as advocates for it (which seems to be a rare thing – it was at least seldom found in the contemporary music environment in which I grew up).

Now, mainly through personal contact and involvement in performances, there are also a number of musicians of a younger generation who take Wandelweiser as one of their starting points. As influence is such a tenuous thing, it would be hard to know where to begin or to end a list of these musicians. It’s probably best to say that, for a group of younger musicians, the music of Wandelweiser is a part of the experimental music atmosphere in which they learned to breathe.

The recent compact disc recordings are, as in the past, not an extension of, but a complement to the concerts. As mentioned above, many of the more interesting EW discs represent things that could never have been performed as such. To choose recent examples, both Antoine Beuger’s

too, with recordings of separate duos made in Düsseldorf (Jürg Frey and Irene Kurka), and Tokyo (Rhodri Davies and Ko Ishikawa) combined to make a new piece out of two other pieces — and the duo field recording performance disc by Manfred Werder and Stefan Thut do not represent possibilities available in a concert space (

Im Sefinental). My two most recent discs on the label are also examples: both realizations of

an unrhymed chord were specifically designed as recordings, and

hearing metal 1 is a work for recorded percussion to begin with.

It is here perhaps that the music of the Wandelweiser group shares something with some interesting recordings on labels such as

Erstwhile,

Improvised Music From Japan,

Slub Music,

Hibari,

Another Timbre,

Manual,

Cathnor,

Confront,

Potlatch and others that seem ostensibly more concerned with improvised music. Recent releases on these labels also often confound notions of live and recorded means, and blur the line between what has been spontaneously invented (or improvised) and what is composed (or assembled) in the studio. Perhaps this sense of shared territory is one of the reasons that EW releases have found a successful outlet in the US in Erstwhile distribution (erstdist).

I’ve recently started thinking about how much overlap there is between these apparently different enterprises. It is not uncommon for improvisers these days to limit or fix aspects of their performance before playing. One might set a total duration beforehand (as Radu likes to do), or bring only a certain limited set of materials or an (apparently) limited instrument (such as Sachiko M’s sine wave sampler). Or perhaps an improvisational work might find itself in a context where composed works have also been played (a practice which AMM has long engaged in). Recently in concerts and on recordings, works by Sugimoto or Cage might be understood as belonging to “repertoire” of an ensemble that most often improvises. While I think it’s fair to say that something is being shared by these various musical streams, I would prefer at the moment not to name what that is (in part because I have no idea what to call it). At the moment I feel that this unnamed area has a tremendous potential going forward.

Non-national musicDespite its base in Germany, Wandelweiser is not a national style or trend. It was remarkable that people from Austria, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, Brazil, Korea, Japan and the US felt they had much more in common musically (and often personally) than they did with their own countrymen. The American experimental tradition was gone (or at least, not a part of our generation) and this was being replaced by something else. Whatever it might be called, it was certainly not the province of one national way of thinking about music or making music. Outside of the countries where the members of Wandelweiser live, there have been a couple of strong developments in the last several years.

For nearly ten years now a set of shared musical activity has existed between many members of Wandelweiser and experimental musicians in the UK. My wife Kathy and I had the opportunity to get to know something of the scene in London in 1996. As she was there doing her dissertation research on the Scratch Orchestra, we had the chance to meet and talk to John Tilbury, Howard Skempton, Michael Parsons and many others (and we heard AMM live for the first time in Chicago not long thereafter). During our stay in London, I learned of the music of Laurence Crane, who I managed to meet on the next trip over. Shortly thereafter, Manfred Werder came into contact with two composers with whom members of Wandelweiser have since often worked: Tim Parkinson and James Saunders. (To this list of UK collaborators, I would also add composers Markus Trunk and John Lely, though this list is growing rapidly.) Members of Wandelweiser have performed at INSTAL (Glasgow) in both 2008 and 2009, and this has led to more contact with the vibrant experimental improvisation community in the UK and elsewhere.

Radu Malfatti had of course lived once in England, but is, as usual, a special case. Since his musical shift, many of his friends from that earlier era were no longer on speaking terms with him. However a whole new set of associations with a younger generation developed – mostly improvisers, in London and Berlin, who looked to him as a trailblazer in a new style of making music. (There are simply too many names here to mention!)

The Tokyo ConnectionTo close this section, I’d like to say just a little about the relationship that has developed in recent years between Wandelweiser and some musicians from Japan.

Some of these, in retrospect, had something like an aura of inevitability. Certainly, to choose one example, Toshiya Tsunoda’s somewhat “hands-off” approach to field recording (already present in the very beautiful recordings of 1997) — something I think of as steady state recordings of silence — are not so far away from thinking we in Wandelweiser might have recognized (had any of us known of it then).

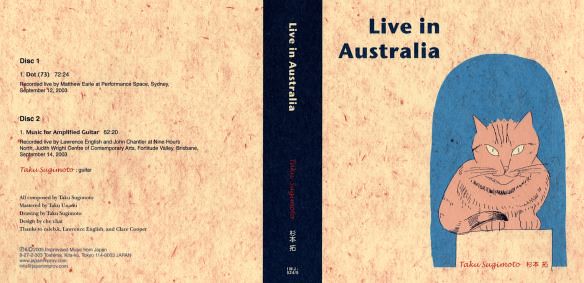

When Taku Sugimoto first contacted Radu Malfatti in July of 2000 it might have come more or less out of the blue, but if one looks for a moment at the music coming out of Tokyo from at least the mid-90’s onward there is a sense that there too something radical, having to do with the fundamental nature of sound and silence, was at work. The world of

Opposite is not so far from that of

Beinhaltung, that of

The World Turned Upside Down not so far from the one of

Dach. In any event, as their work together (such as

Futatsu) amply demonstrates, there was a quick understanding between these two great musicians.

When Taku Unami began distributing Wandelweiser discs through Hibari in 2004, the music became much better known (and apparently, appreciated) amongst experimental musicians in Japan. Both Radu and Manfred (starting in 2004) have worked there several times, along with, most recently, Antoine. In a short time some beautiful musical projects between these musicians have developed — including most recently some wonderful recordings: Manfred Weder’s

20061 on Toshiya Tsunoda’s Skiti label,

A Young Person’s Guide to Antoine Beuger (produced by Sugimoto for his Slub Music label), and

kushikushism, a duo project by Radu Malfatti and Taku Unami (also on Slub Music).

Antoine told me a story that may or may not be symbolic of the way in which Wandelweiser is understood in Japan, especially amongst younger artists. When Manfred, Radu and he visited Tokyo in November of 2007, Antoine received many discs, often without any labeling, from young musicians. One particular musician gave him a few, explaining in each case, which ones were “more Wandelweiser” and “less Wandelweiser.” On one of the “more Wandelweiser” discs, there appeared to be no sound at all.

As I’ve become acquainted recently with much more of the music made in Japan by experimental musicians from the “onkyo” group and its offshoots, I’ve returned to the thought behind Radu’s comment above many times. Sometimes the concerns, if not the music, seem so similar as if to be almost identical: as if a group of ideas was circulating of which no one was directly conscious – as if they had no real point of origin and were able to place themselves anywhere they could find a “host.”

In the music of Sachiko M and Toshimaru Nakamura there is (or can be) such an intense stillness. Where does it come from? How available is it to others? In the work of these musicians with Keith Rowe I find an inspiring parallel to some of the music I got to know with my Wandelweiser friends. To be sure, there are many differences: the prevalence of electric over acoustic instruments, the fact that the music is improvised, and the various lineages that the musicians have within their traditions, to name the most obvious. Nonetheless, the stillness, the silence and the serene beauty; the sense of taking your time and trusting your audience to take the time with you; the evolution of the work and the sense that an active exploration is going on; to me these suggest a deeper kinship. Perhaps the most representative (and beautiful) example of this is the work of these three (with Otomo Yoshihide) at the incredible concert in Berlin on May 14, 2004, documented on

ErstLive 005 – particularly on the final disc.

When I think about our group now, and especially the large set of friends of this music, I wonder if some of the most fragile seeds planted in the mid-century, by Cage and the experimental tradition, by the certain subgroups within free jazz and improvised music communities, and by the quiet experimental tendencies in Japan (Toshi Ichiyanagi, Yuji Takahashi) have, after spending many years underground started to spring to life: invisibly – everywhere.

Summer/Fall, 2009I would like to thank Jon Abbey, Manfred Werder, Radu Malfatti and Antoine Beuger for their help with this article.photos/credits:

1. the wandelweiser composers ensemble (joachim eckl)

2. antoine beuger (hartmut becker)

3. john cage (ben martin)

4. jimi hendrix (photographer unknown)

5. desert plants (unknown)

6. stones (CD cover/ida maibach)

7. zionskirche (unknown)

8. christian wolff (unknown)

9. gilles deleuze (still from French TV)

10. radu malfatti/mattin (yuko zama)

11. mauser in his studio (marianne hambach)

12. sonnenzeichnungen (nicolaus) (kathryn pisaro)

13. marcus kaiser (in sook kim)

14. kunstraum (with eva-maria houben, john mcalpine, michael pisaro) (renate hoffmann korth, ew website)

15. wolff.beuger.frey (silvia kamm-gabathuler, ew website)

16. sachiko m/dan flavin installation (yuko zama)

17. taku sugimoto/radu malfatti (eleen deprez)

18. keith rowe/sachiko m/toshimaru nakamura/otomo yoshihide (yuko zama)