in November 2010, Keith Rowe and Radu Malfatti met at Amann Studios in Vienna, where they played together for the first time ever in their lengthy careers. both musicians have extremely strong opinions and perspectives, sometimes conflicting and sometimes agreeing with the other. over the course of the week, many fascinating discussions were held, and at the end of the three days of recordings, I asked the two if they'd be OK answering a few questions. all of us were a bit on the tired side, having just finished recording three CDs of widely varying material in about a 48 hour period, and so this shouldn't be regarded as any kind of in-depth interview, but more a version of what you might have heard if you sat at our table in the cafe next door to Amann in between recordings.--Jon Abbey

Abbey: So, both of you guys have been involved with the world of free improvisation to different degrees for four decades or more. Why originally improvised music and not composed music?

Rowe: I think, in my case I was ill-equipped or non-equipped to perform music from scores. Because what I do actually in some respects has very little to do with music as we know it. I mean, the process on the table is the process from painting, from the plastic arts, everything on the table is justified primarily by visual arts. So, though I did in life later actually study music, I didn't at that point where I started to play, improvisation was the only open avenue.

Malfatti: It's true, it's the same for me really. First point, I'm not well enough equipped to perform the so-called composed music, whatever that is. I mean, not classically, not contemporary, but I started off with Dixieland and that was what interested me the most. I played some stupid pop songs of the fifties on accordion or something, and then I heard Dixieland on the radio and I thought like "wow, what is this? fantastic!".

Abbey: When was that around?

Malfatti: I must have been, I don't know, 10, 11, 12. Which was almost unheard of in Austria, in Innsbruck, and it was kind of an avant-garde feeling. So I was interested in that, and that carried on for a very long time, and only after that, when I started to hear Anton Webern, for instance, which you have to in Austria, then suddenly there was a world of music, which, I mean "wow". Like the first time I heard Dixieland, "wow, what is this? fantastic!". The first time I heard Monk, I thought "this is horrible but so fascinating", I was like a bit scared and I was like "who is this guy? I have to get more."

And the things I am doing now, with this Wandelweiser group, again, it's not the classical, well-trained, obvious virtuoso people who are doing this kind of music and this is as fascinating as when I heard Monk for the first time. And I tried to play like Monk, I tried to play like JJ Johnson, I tried to play like Jack Teagarden, I tried to play even like Kid Ory, and it never happened, of course, you know, because I am a white Tyrolean (chuckles). But basically I agree with Keith, it's the same reason.

Abbey: The followup is for Radu, which you just touched on a little bit, what specifically changed for you around 1990 (or whatever year it was), when you withdrew from the improvising scene, and moved into Wandelweiser and the group of people that you've been a part of ever since?

Malfatti: First of all, it didn't start in the nineties, it started actually before. And I think it is the fact that I found that so-called improvised music came to a halt, a stagnation in evolution and it became very very idiomatic, I found. And there were certain things that are not allowed, because you are "free".

Abbey: When do you feel like you felt that for the first time? What year do you think that was?

Malfatti: I don't know, you can't put it down on like Friday morning or something. I don't know, must be early nineties somehow. I can't put a finger on it, but it was an organic evolution for myself, "why is that not allowed?". Actually I even talked to John Butcher about it, with 'News from the Shed', you must know when that happened?

Abbey: 1989, I want to say.

Malfatti: OK, yeah, yeah. And he was very young at that time and we were talking about it, because in improvisation with 'News from the Shed', we quite liked to play unison, long notes in unison. And then, once I said, "you know, it's very interesting, it's such a wonderful sound and it seems you're not afraid of playing the same note and I don't seem to be afraid", and he said a fantastic thing. He said "yeah, the first generation, they seem to be afraid of the obvious." I thought it was very nice.

So, gradually, you know. And then I had this orchestra, this 13 piece Ohrkiste, and I was working with them already and I still wanted to work with the improvisers because they were not only close friends but also I liked their images and language. But what I tried to introduce was things which were exactly that, things which were not allowed in free improvisation, to actually do something and build something up, and then everybody comes in at the same time doing a certain thing. And, that made me a lot of enemies actually from the improvising scene.

And then more and more and more I came to a certain point where I knew, I knew what I didn't want to do anymore, but I didn't exactly know what I wanted to do. So, you might know this concert in Italy with Gunter Schneider and Burkhard Stangl? And we did a trio improvisation, and I was talking to myself, thinking, which I normally don't do, and I said "Why are you doing this? You don't want to do it anymore". And at home, I didn't, but then on stage, the familiar situation, boom, I went straight back into my old clichés. And I didn't want to do it anymore. So I went home and I wrote a piece for myself where I left all the things out. I didn't want to but on stage, I still fell into it. And the first time I played this piece in public, it was hard, it was so hard.

Abbey: Is this the solo piece on the Wandelweiser CD?

Malfatti: Exactly. But that changed again, in the first version there was still much more which I had to rub out. But, because I had the notes, and I wanted to play what's there and every now and then I felt "now I would like to do this", but then I told myself "no, you cannot." So that was a very interesting fight against my own routine, which I'm very interested in.

So that's why I love to talk about today, much more than what happened in the past.

Abbey: Keith, you answered this somewhat already, but I know that you're a student and a lover of many eras of classical music history. So why, even going forward past the beginnings in the sixties, past when you studied with Michael Graubart, why have you chosen to express yourself almost entirely via improvised music, and maybe more interestingly, is this something you've found yourself questioning in recent years?

Rowe: I mean, improvised music, I go along with the term, because I don't actually have another term for it. I actually don't like the term "improvised music" very much. I think that if I'm honest there was a period where I thought maybe it was a legitimate term and maybe I could see what my dear friend Eddie Prevost meant and he was probably quite right at one point to actually emphasize improvisation's importance and its quality, because it was not recognized. So I think to give it some kind of recognition, some kind of status, rather than "well, it's only improvised", it's something that was very important at a point.

But I would say for the last 20 or 30 years, you would very rarely catch me using the word, but I'm forced to use it in a way, because I don't think I have another term.

Do I question it? Yeah, of course. Of course, because I know emotionally and intellectually why for me, the guitar had to be laid flat on the table, to be detached from myself. I understand, I didn't copy it from someone, I really understand that process. And in a way that process runs directly opposite to the conventional way of thinking on how you should play the guitar, how you approach the guitar, and then consequently what music comes from it. So driving me since I was in my late teens, driving the agenda towards more and more and more abstraction, reduction and abstraction, reduction and abstraction, it's who I am, it's what I am. And I know it from those standpoints, I know it from music, but I also know it from visual arts, and philosophy.

That doesn't answer the question, does it? (chuckles)

Abbey: You've both obviously been invigorated and inspired by the younger generation of Tokyo musicians. Can you each talk a little bit about that, how initial contact with their work affected you, and how you think your ongoing collaborations and contact with them has changed your own approach?

Malfatti: Hmm, it's an interesting question. I don't know, I don't know, did they influence me? I don't know. I had the impression that we met exactly at the same level, I might be wrong, maybe they think differently. I get a lot of food for thought from them, but I don't think more than from other people. To me, they are very very interesting, but I had the impression that we met actually on the same level, in a way of understanding. And Taku Sugimoto, he came up to me one day, and he said "Hello, I'm Sugimoto-san and I like your work and maybe we can do something together." And then the first time we played together, it just clicked. I thought "wow, now this is improvisation again", I don't have a problem with the term of improvised music. I had problems with a certain kind of improvised music.

But for me, there is quite a big difference between improvisation and written music and I think we realized that today and yesterday, the difference. Because Jürg Frey's piece, we never would have improvised in that way, because it's really a specific thing. I would say the same with 'Pollock '82' because I was actually really following the score, and I didn't want to add anything, and I decided I'm going to only use the white noise, the breath and then interpret the signs. And with improvisation, what we did now, I wasn't even thinking or feeling in that way, and looking, "now this will appear" or something. It's a completely different emotional situation to me. So I don't have problems with the terms.

And with the Japanese guys, maybe there is a certain aspect in their culture which appeals to my understanding of their culture, because we don't really have it in Europe. There is some, of course, and in America, as well. So I don't know about the influence, who influenced who, and I don't know if it's important. Not more than if I talk to Keith or play with Keith or talk to somebody else, there's always a mutual and even contagious thinking.

Rowe: Well, I think for me, the important Japanese influence, I think the first one, was having an invitation to see a demonstration of zen archery, when I was about 24, in London. It was part of a secret society, and we also had an invitation to go and see a Gagaku orchestra, both those things were very important. And then that Jac Holzman recording of Japanese classical music, so I'd say the mid-sixties were the start. And then through Cage and conscious rejection of rhythm in favor of pulse, which again came from Japanese and Chinese music. For me, I have to conflate Japanese and Chinese because we were very very influenced by Chinese thoughts and the book of Joseph Needham's, "Science and Civilisation in China", to the extent where we actually learned Chinese and to speak a little bit of Chinese and to write it in preparation for "Treatise".

So all that came way way way way way way way before, and I think I would concur with what Radu is saying. Toshi is the first major person I interacted with and I would say it was the same experience for me, it was like meeting a brother, a musical brother and we just clicked.

Abbey: Well, that was 2001 or 2000, but before that there was the Sugimoto record you heard and working together a bit with him, the session in London and the concerts in France and in Wels? You've talked to me before about when Julien Ottavi played 'Opposite' over a club speaker system in Nantes, about the effect that had on you.

Rowe: Well, that's right, one could say that how one is influenced, one way of being influenced, is that people give you permission to do things. I always feel that Cage gave us permission to do something...

Malfatti-Yes.

Rowe: And I think the permission-makers...

Malfatti: And you can get permission from other people as well.

Rowe: Absolutely, absolutely. And I think that's one of the very important things in one's own life is to pass on permission to other people. It's very very important thing that we do. So when I heard Taku's recording for the first time, it was like a permission to think about doing that.

But I've said to you before, that when I first played with Toshi, it was almost as if I'd been hanging around for thirty years (chuckles) waiting for someone to turn up where I could actually play like this! Because I couldn't play like that in AMM, I couldn't play like that in any other situation, I could only... Maybe it's not strictly true, but I didn't meet anyone.

Abbey: Yeah, I have that note you sent when we were finishing Weather Sky, where you said almost exactly that. You wrote "in many ways it's a kind of music that I've waited to make for 30 years, but there was never anyone who felt the need to do it".

Rowe: Yeah, exactly.

Malfatti: Right, same here. Very good.

Q; Yeah, that's kind of what I was driving at for both of you. Maybe there wasn't an influence for you, Radu, or no more of an influence than from anyone else, but it does seem like some of your strongest collaborators now come from Tokyo. And I'm not saying necessarily influence, but it's always nice to have collaborators, and it must have been invigorating to find Sugimoto and find someone who shared...

Malfatti: This is certainly true, this is certainly true. Yeah, yeah. And because of the old idiomatic way of playing, actually I stopped almost 100 percent and I was together with the Wandelweiser people and that was fully satisfying for me. And I had to learn how to play this, this was not easy, it was not easy to begin with. I had similar or sometimes the same idea of what it should be, and then I met Antoine (Beuger) in Cologne. And it was a little bit the same, it was like "wow, there is this guy who does what I want to do". So I got more and more into that, and improvisation, I put that aside.

And then when I met Sugimoto, I hadn't heard any music of his before. So the first time we played, that was the first time I heard him, even though we'd met a few times. And that was the first time I heard him, and I was really like "whew, wow" (Rowe chuckles), so in this way I would love to improvise again. But it's not really an influence...

Abbey: It's not really an influence, it was the invigoration.

Malfatti: It's like Keith, I was waiting. I was waiting for somebody, and then great!

Abbey: I remember reading your Improvised Music from Japan back and forth and thinking it was like you found a brother, like you found someone who shared your belief system, from halfway across the world.

Malfatti: That's right, yeah. Fascinating, isn't it?

Abbey: Over the last few years, my perception is that 'our music' (whatever that may be) has moved away from collaborative improv being the primary driving force and more and more towards solo work and composed music. Do you feel that's accurate, and if so, why?

Rowe: One thing that one might be trying to attain is some sense of clarity in what you're doing, and I think it's certainly true that if you're solo, you have the clarity of who you are. You know what it's like, when you're in an ensemble, you can be doing something that you're really interested in following a path that you want to develop, and someone will do something which totally wrecks it. And if you're working solo, then you have this chance of this particular kind of clarity, and obviously composition too.

But maybe it's also the fact that we're just balancing. Maybe so-called free improvisation is something that historically can't go on and on and on forever, it needs to be balanced out with some other thing, so the improvisation would become more sparse after this concentrated, in-your-face, full on, high volume maximum amount of information and it's quite often in the arts that you'll swing to a different perspective. This is all very healthy, you know. And I think at the moment it's going in a particular direction, but as sure as eggs are eggs, in 5 or 6 years time, it'll go back to some fully saturated world, where the investigation of silence which we've undertaken in the last half century or something like that will have exhausted our interest for the moment, then we'll move on to pitched sounds or non-pitched sounds or orthodox sound production. It will move. It won't stay like this.

Malfatti: I think it did already, actually.

Rowe: Yeah.

Malfatti: The only thing is, about the solo. That started much earlier than...

Abbey: Yeah, I'm not saying that there were no solos.

Malfatti: Yeah, of course, there always were solos.

Abbey: I guess my issue is you can have a clarity and control when you're playing solo and someone isn't going to mess you up, but the flip side is you're much less likely to be pushed into an area that you wouldn't be pushed into otherwise. My own taste is towards collaborative improvisation in an ideal world, because of that, because musicians can find themselves pushed into places that they've never gone.

Rowe: Well, you need both. I don't think anyone's advocating that you only do solos.

Abbey: Sure. I guess the point that I'm driving at and the point where I was going to with the next question is that for me, we've almost gotten to a point, and Radu may have felt like this a while ago, but for me it's come in the last couple of years, where I almost feel like it's impossible, or close to impossible, to make a great collaborative improvised record anymore. Of course, I'm saying that an hour after we probably just did that, but I think in general, it's very hard. When I look at what's come out in 2010, there's less than a handful of records like that, and for me, that's the issue. Of course, there have always been solo records, there's always been composed music, there's always been collective improvised music, there will always be all of them. It's a question of which are more interesting and which are actually doing something, and to me the balance there has shifted in the last few years. And I guess what I wonder about with your perspective, because this is my perspective: do you really think it's possible that an area like free improvisation which theoretically at least has an incredibly wide range of possibilities, I mean it's not jazz, where there are defined boundaries. So despite this seeming openness, do you think nevertheless that we've come to the end or are coming to the end of that era?

Malfatti: Well, first of all, I don't think so. But maybe the definition is to be questioned, but again, that's why I really don't distinguish between composed music and improvised music, because you have very boring composed music, obviously, and you have compositions full of cliches of the cliche of the cliche of the cliche, and you have that in improvised music as well. The most interesting part for me today is what are the three most important aspects in music, but not only in music, in different areas as well, is the material and the structure and the form. So the material was a very very interesting topic, let's take Helmut Lachenmann, but there were of course other people before. So he is talking about "klangzertrümmerung", which means "the scattering of sound", and he didn't want to have a clear note anymore. The thing is, the structure of his pieces, they were actually very old-fashioned in a way. He had sonata structures, I'm not talking about the form. So one of the first people who really took care of a new understanding of structure was actually Cage, and his compatriots. And so now I think my main point of interest is the structure. I'm not interested so much anymore in the material; it can be noise, it can be sound, it can be distorted, it can be a very clear sound, a very clear note on a traditional instrument.

But what do I do? I have a big space, and I decide I want to build a house in it. And then there are many possibilities, I can build 273 rooms, so every room is just a square meter or something, I can decide I want 3 rooms, or even just 1. So the form from the outside is still the same, but the structure is what you are doing. But for me it is like I have a sound, a note or whatever, a sound, and how do I structure it in relationship to the other sounds. So in that case, with a full understanding, I wouldn't be afraid at all to do a collective improvisation with 20 people, if those 20 people have a similar, not the same, but a similar concept of structuring. Which means, in other words, there is no single way of thinking, there is no "let's fill this space", there is no "what else can I do?", but for the sake of the overall building and produce your sound and willing to listen to the other sounds for half an hour maybe. And I don't feel the need, that there is something missing and I take the opportunity to be listening to other sounds, and this for me is what is very interesting in composed music if it has the same aspect. One building with one or two big rooms, instead of all the little cells in prisons, maybe even locked doors.

So for me this is the most interesting part, and therefore I don't see a very big difference between improvised music and composed music, because in composed music you can arrange the sounds in a specific way. In improvised music you can as well, but you really need all the other people with the same understanding, the same feeling. But that's nothing new, because that always has been like that, even in free jazz or Dixieland, you need the people to produce a certain thing. So as I said, I think the main topic, the main interest, is the space and the structure of how to place rooms or commas or sounds. For me, this is the most interesting bit today.

Abbey: That makes a lot of sense.

Malfatti: And that's why you don't find it very often., because most of the people, they are just busy to fill up the space, the structure, fill it up, fill it up, fill it up. I don't want to use the term "Louder, Higher, Faster" because that's 30 or 40 years old, but then it was in a positive way and now it would be a criticism.

Rowe: Yeah, I think for me, likewise, I don't have a distinction between composed music and improvised music. It's why I have a problem with the term "improvised music" because I'm not sure how much of it is actually improvised.

Malfatti: But you don't have a better term, so you might as well use it.

Rowe: Yeah, exactly. But for me there is just music, there is only music, there is just this term we call "music", even that is slightly problematic. Because I liken it to if I walk into an art gallery, there are paintings, and it doesn't matter to me if the painting was made in 1350 or 1628 or 1922 or 1956, the work needs to resonate with me to have significance or meaning or whatever you want to call that. And it doesn't matter what the genre is, the genre of painting is for me not relevant.

So I think it's true too with music, that I'm not really worried about what the genre is. But my experience is that there are certain areas of music which I just find more rewarding to spend time with, like Haydn's string quartets, Bach-St. Matthew Passion, or David Tudor playing John Cage-Variations II or John Tilbury playing Bunita Marcus or Horowitz playing B Minor Sonata in St. Petersburg. That's the only thing that interests me, is the quality of the thing, and I'm really not worried about how it's notated, how it's written and all of that.

Malfatti: I agree, yeah.

Abbey: Fair enough. The rest are hopefully more interesting questions (chuckles all around)...

Where (and obviously you don't know, but I'm asking anyway), where do you think our music will go in the next year, five years, ten years? Do you see any new galvanizing force like (at least in my opinion and I guess for your guys also) the Tokyo musicians were?

Malfatti: First of all, I have no idea where it will go. Second, I'm not really interested. Third, it's impossible to know. You could ask me how the weather will be in April 2012.

Actually I'm almost quoting Monk, I think, and somebody asked him a similar question and he said "I don't know, even if it goes to hell, I don't care. It's now that I'm interested in." So I have no idea, and it's impossible to know, I don't want to know, I can't know, and I would hate to make any predictions.

Rowe: Yeah, I mean, of course, it's really really difficult to know with any certainty. I suppose that one can say with certainty that 98 percent of it, like the music of any age, will be garbage.

And I think the problem is if you're working quite hard on what you're about, if you're consciously participating on what you're about. I've said in other places, if you have your nose so close to the canvas, that it's actually very difficult to be objective about other people's work, let alone your own work, and very difficult to track what's going on. And I'm not a promiscuous type, so I don't have lots of info flowing into my system which will lead me to know with any certainty what's going on.

I just think, though, and maybe I share this with Radu, that probably the most important thing is to keep moving in your own world, keep discovering, keep learning, pressing the refresh button, trying your very very best not to slip into bad habits. And that would be true for every artist of any distinction, any musician who takes their craft seriously, whether you're playing Bach or whether you're playing whatever it is. It's the same issues for all of us, we all share the same issues.

Abbey: Just to follow up, and maybe you answered this already Radu, and if you did, I'm sorry, I wrote these out before.

But just the same exact question on a personal level instead of an overall level, where do you see your own music going in the next year, 5 years, 10 years, if you have any idea?

Malfatti: Same answer. Same answer, really, I have no idea.

I'm curious, I'm curious about it and I'm looking forward to see what's happening and hopefully, probably not, but hopefully, I would love to change again once. Actually I don't think I'm trying to change, I don't want to change the world, I don't want to change anybody, maybe myself. Rather I'd say I'd like to be alert and aware, and really feel and observe very closely and critically my own doing, my own thinking. Probably it's enough to observe it because we all change, and usually people who stagnate, they don't allow themselves to observe themselves, because they move already, but then they say "no, I'd rather stay here where I'm used to, that's my field where I'm comfortable". But I think if you're really alert and aware of yourself, then you might change anyway. Probably.

And if it comes to a point where I have the feeling "wow, I feel another change coming." I'm probably too old for that, but it would be great if I could experience that once more the way I did 20 years ago and 40 years ago and 60 years ago. I thought I had three, to me, major changes in my musical way of thinking, even though the first one I wouldn't call it a change because I grew up in a certain way and I was rebellious enough to try to break out and it was a necessity more than a conscious change. But the last one was not a very conscious change either, maybe. It was a necessity, it was a saturation. As I said before, I knew I didn't want to do this anymore, but I didn't know what I wanted to do, where I would go.

And if I'm lucky enough to get once more to that very shaky line of uncertainty, "where am I going now?", I would be very grateful. But I'm looking for it, and I can wait, and allow myself to do it again.

Rowe: Well, of course, for me I suppose the most drastic kind of change was very early '66 where we formed something called AMM. Both in terms of that very difficult, finding a completely new language for your instrument, it's quite a difficult thing to do. It's very hard to keep doing that, I imagine very few people do it once, let alone one person doing it a number of times.

It's kind of interesting, I remember sitting on the seafront with Eddie down in Marseilles, a long long time ago. He looked at me and said "do you think we'll ever be involved in another musical revolution?", and I said "no, probably not". But I think in a way there have been other minor ways of working, so for instance the sound world like what we did today, particularly in the improvisation, which we're wholly responsible for (as opposed to the composed pieces, which we're only partially responsible for), I think there's a kind of change in the emphasis of the language, the degrees of abstraction, which comes as a result of everything else that has happened, but it's actually quite a complex subject to try to unravel.

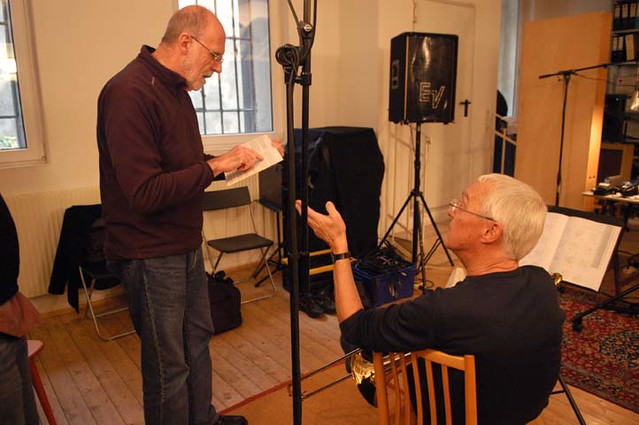

(Photos by Yuko Zama)