I guess ErstLive 007 starts with an invitation from Jon Abbey and Yuko Zama for me to participate in their AMPLIFY: light festival in Tokyo September 2008, and that I would be the only non-Japanese performer.

The concept for my solo performance was only formed the night previous to the performance itself. Thinking about the forthcoming solo, I felt the need to somehow make clear “who I was”: what my background is, what are my concerns? Something about my interest, the music I love, the sounds that have influenced me, during the performance I came to realise these could be regarded as “Cultural Templates”. Also important was the desire to feel a freedom with regard to the performance’s shape and content, along with the freedom to break rules. For almost half of the solo’s duration, I utilise long sections of pre-recorded classical music unprocessed, unaltered, and presented as it is, I considered this a break from the normal expectations.

The overall form of the performance came from Jackson Pollock’s 1952 painting “Blue Poles” although my performance would only reveal “Four Poles” (the four cultural templates which form the focus of the performance. During the three or four months leading up to the Tokyo festival, I had decided to revisit techniques from the past that I had abandoned. For the festival I had decided to resurrect my obsessive use of clear plastic lids from the mid sixties, along with a bow from the same period, and from the early eighties the steel pan scrubber.

The solo starts with the pan scrubber, clear plastic lid, and contact mike. I wanted to commence with a playing style that could be interpreted as inept or clumsy even, to have the feeling of a deliberate paucity of means as well as openness, that would both refer to earlier periods of my playing (late 1965-middle 1966) but also retain its asceticism.

At 2:14 is the first of the cultural templates, Alessandro Marcello’s Concerto for oboe in D minor (c. 1717). This piece, like all the templates, can be regarded as multi-dimensional or multi-layered. These dimensions/layers in the Marcello refer to:

the artist in society

solo with accompanist

point and line

point and mass

centre line in Treatise

my role as basso continuo in AMM (rearmost wheel in the Yellow Truck 1966 AMM image)

the soloist melancholia sense of loss (which bookends the Purcell lament at the end of the piece)

how the instrument is “touched”, the sensitivity of touch

its binary nature

translating material between forms (difficult to describe, an art school task is to move the colours of a still life painting one notch around the colour wheel, blue becoming violet, red shifts to orange, yellow becomes green, green becomes blue, etc. A similar exercise would be to hear (translate) Django Reinhardt’s guitar as a soprano saxophone.)

Appreciating the oboe here as Sachiko’s contact microphone, meaning … to listen to this oboe recording but somehow translate it into the sound of the contact mike, or steel pan scrubber, and therefore hearing the orchestral part as silence, or amplified silence, or silence made audible. This was an early AMM technique to make silence audible, which explains how I never thought of continuous sound as drones but as degrees of silence made audible. The rejection of excessive ornamentation and ostentatious display again refers to an early AMM decision to reject gesture, to perform as with little or no bodily movement. Towards the end of this template (around 4:06), I accompany the template with very gentle pan scrubber as if to say “when using our abstract sounds, pan scrubbers, knives, contact mics, etc. we should touch and approach those materials with the same consideration, sensitivity, musicality and sense of occasion as if we were this oboe player."

At 5:01 the template ends, the steel scrubber continues and at 5:36 my human fingers touch the string and sound a single note, followed at 5:43 by a physical movement and sound which represents a time line. The time line technique comes from Cardew's Volo Solo, a difficult piece written for John Tilbury. At some point in the piece, John was obliged to produce around one thousand notes in a very short period. Fascinated by this challenge, I set out how to produce a thousand sounds in as short a period as possible. I achieved more or less a thousand sounds in between one and a half to two seconds, using a one metre steel ruler with a thousand millimetre engraved marks, and running a contact microphone attached to a stylus. This technique came for me to signify time, the passage of time, and here the single note at 5:46 is juxtaposed with a timeline of about 250/300 sounds. My intention was to echo the solo/accompaniment relationship found in the earlier template, reinforcing the reference to Wassily Kandinsky’s 'Point and Line to Plane'.

6:25 refers to the sound of drawing, in an attempt to link the act of drawing with musical performance. I’ve attached a contact microphone to a piece of charcoal, and literally draw around the objects on the table in front of me, in a sense confirming how I regard my musical performances as acts of painting. This is also the first appearance and foreshadowing of the death motif, which is created by a handheld battery powered face fan with its propeller fan modified. Its long menacing sound is combined with a rubbing sound from a contact microphone, the rubbing sound represents human society, the physical (and other) contact between people, at times the rubbing is affectionate, and at other times there is friction. Again, it’s the juxtaposing of long and short sounds.

7:51 is a single note, which leads to a recapitulation of the opening section, the steel scrubber and a clear plastic lid. Perhaps I might say more about the clear plastic lid: it’s a reference to Duchamp’s 'With Hidden Noise' but here I’ve reversed the process, revealing the content, which is the steel scrubber.

Reading the sleeve notes of AMMMUSIC (June 1966) Electra EUK-256, “Seeing as for the first time this reddy brown object with all the strings going away to the left, a bow going across on the right hand side and interwoven amongst the strings various little things, on top of that a plastic lid, and you just watch the sound happening”. Seeing the sound happening is something which has been with me for a long time.

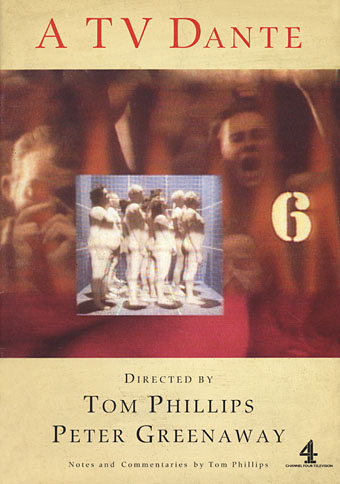

8:29 we enter the world of “affectation”. The detuning here refers to Dante’s Inferno (particularly the Tom Phillips/Peter Greenaway version). The technique here is a live radio broadcast is picked up and transmitted through the earpiece to the guitar pickup, which picks up the broadcast and passes it through to a Boss PS-3, which for me is a way to achieve a form of “affectation” and process. The voices and music of popular culture swirl around, it’s a world without focus, the sound is overprocessed, distorted and overwhelmed by its overprocessing. This is the world I feel we live in.

9:40, hovering above the Inferno is the second template, Jean-Joseph Cassanea de Mondonville, Grand Motets, Dominus Regnait, (c. 1735).

This template for me poses the question, "What is profundity in the digital age?" If I reflect on other music from the early/mid 1700’s, we find the dominance of the viola da gamba is being challenged by the cello, as described in the writings of Hubert Le Blanc (Défense de la basse de viole contre les enterprises du violon et les prétentions du violoncel, 1740.) Le Blanc’s comments recall the later critiques by John Ruskin of James McNeill Whistler in 1878 where Whistler's paintings reflect a fusion between painting music and Japanese culture, and more recently in our own circle's critiques of amplification, electronics, computers and sampling.

Listening to Jean-Baptiste Barrière's 'Sonates pour le violoncelle avec la basse continue' (1733), it seems to me that there are aspects of the violoncello’s sentiment that are not available to the basse de viole. It's not a question of better or worse, good or bad, it's about new sentiments, new relationships. Which leads me to question what are the new sentiments? emotions? Will only the artist and creator of the new recognise its importance? This template is also about how we develop out of the past, how we make the past serve the present.

Clearly the template is about significance and profound meaning from the culture I originate from, my feeling is that this profundity is not universal. In my solo performance here in Tokyo I hold this template high and clear, with a minimum of interference. What I do add to the template are remnants of the inferno below, the dirt and grime of everyday reality, but what should people hearing these templates make of them?

How I listened to the templates during the performance varied. Mostly I imagined in my mind's eye that the significant points suggested by the templates were on transparent sheets. I would conceive that the sheets were laminated on top of each other, perhaps combine all the significances and concepts as one solid mass. Another possibility is to dart around in rapid succession from point to concept to significance to idea in a blizzard of thoughts, or simply remaining on one solitary notion.

12:11 the template ends what follows is a reworking of the plastic lid

12:34 nail/fingers

13:02 single note

13:26 contact mike/serrated edge of knife version of time line through to a steel ruler time line

14:00 steel scrubber

14:25 knife rattle (early technique), again at 14:35, modified at 14:40 onwards.

14:55 return to the infernal, pop radio generally diffused

15:20 knife rattle, again 15:27

15:31 buzzing version of death motif, with knife rattle at 15:44

15:50 single note

15:55 ruler time line

16:31 The third template, Jean-Philippe Rameau, Castor and Pollux, "Tristes apprêts, pâles flambeaux" (1737 and 1754).

This template refers to how revolutions become absorbed. For 50 years after his death, Lully ruled the world of opera in France. This did not change until Rameau presented Hippolyte et Aricie in 1733 to the public, and we now have absorbed that huge revolutionary change and mention Lully and Rameau in the same breath. Sylvie Bouissou writes “In 'Tristes apprêts, pâles flambeaux', Rameau gives a remarkable demonstration of the expressive power of the sub-dominant and the sound-colour of the bassoons that, thanks to him, came into their right as respectable instruments”. So, listening today, that innovation has been absorbed, we hear it as beautiful writing, not as revolutionary.

This template represents the idea that no matter how different, how revolutionary and new we think our creations are, they will become a part of the mainstream, they will become absorbed. Duchamp’s urinal, no matter what observers thought at the time, 100 years later it will be a part of the history of the plastic arts. Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907) and Matisse’s Dance (1909) were both regarded as ugly anti-art and without merit at the time, but are now thought of as possibly the most important and greatest paintings of all time.

Therefore this template poses questions:

Will whatever work we present now, at some point lay alongside all the other works that have ever been produced?

Will our abstract scratching rubbings noise metallic scraping electronic interference glitches need to be placed alongside Haydn?

During the template, I gently overlay our present world, sounds drawn from the infernal. There comes a point at 19:55 where our present concerns drive Rameau away, and the death motif which drifted in around 19:17 with radio dominates, but at 20:35 we regain our purpose, and the template is restored.

21:03 steel scrubber/contact mike

21:38 our concerns about death fade

22:22 the template ends

22:41 re-emergence of the underworld, detuned distant voices, with plastic lid bringing us back into focus

23:04 first muffled collision sound from Boss RC-2 loop station

23:12 second RC-2 sound

23:21 third RC-2 sound

23:43 an attempt to revisit a playing style from pre-AMM (Nov ’65), similar to the deliberate style at the beginning

23:46 spring on pickup sound from mid sixties

23:50 repeat spring

23:54 timeline guitar string version

24:00 knife scrub over pickup variation knife/spring/contact mike/lid

24:46 spring, again at 24:51

25:00 entrance of death motif along with spring, here the fan blades are touching the spring which is in contact with the guitar pickup, also there is a contact mike wedged in the spring, all detuned through a PS-3

25:50 all the elements are brought together, spring/fan/scrubber/radio/timelines/rattles, etc.

27:07 of constant importance: layers of activity, low buzz of distancing alienation, immediacy of news reports, sharp focus click and scrapes, the cheap guitar “poppish” wobble at 27:28

28:01 a line is drawn, dissipating the tension, cutting a new section

28:10 revisiting of an old technique (knife rattle), a constant reminder

about the importance of the past

29:07 a violent re-drawing of the earlier line, re-cutting the section

29:30 gradual development of the death motif, this marks the commencement of the final section of the performance

31:01 beneath the death motif starts the final template, Dido’s lament “When I am laid in earth” from Henry Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas (1689).

Fundamentally this template is about why do we make art? Simon Schama's book of essays, 'Hang-Ups', begins as follows:

"Art begins with resistance to loss; or so the ancients supposed. In a chapter on sculpture in his Natural History, Pliny the Elder relates the legend of the Corinthian maid Dibutade who, when faced with the departure of her beloved, sat him down in candlelight and traced his profile from the shadow cast against the wall. Her father, the potter Boutades, pressed clay on the outline to make a portrait relief, thereby inaugurating the genre (and wrecking, one imagines, the delicate shadow-play of his daughter's love-souvenir)." (http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2004/nov/06/art)

Is this the origin of art? Constable arresting the temporal clouds, fixing on canvas what is passing? The venerable Bede’s description of life as a bird passing through a banqueting hall, in one window and out of another? This CD fixes aspects of the performance from Tokyo 20th Sept. 2008, in many ways the presence of absence.

During the lament the death motif appears at 31:50, 32:50, 33:05, 33:44, these mark the recalling of our own vulnerabilities.

Dido increasingly screams “Remember Me” “Remember Me” “REMEMBER ME” (6 times).

34:50 a deeper more troubled death motif enters as the template ends.

The significance of the template is the question: is a performance, a painting, a poem, an attempt at immortality?

34:58 the deep throbbing drone is reminiscent of the sound I was exposed to as a child during the blitz of Plymouth 1941, lying in a cage at night, under a table waiting for explosions.

36:19 the end.

As I write these notes (Jan 2009) I am horrified, imagining children in Gaza hearing this sound and then silence.